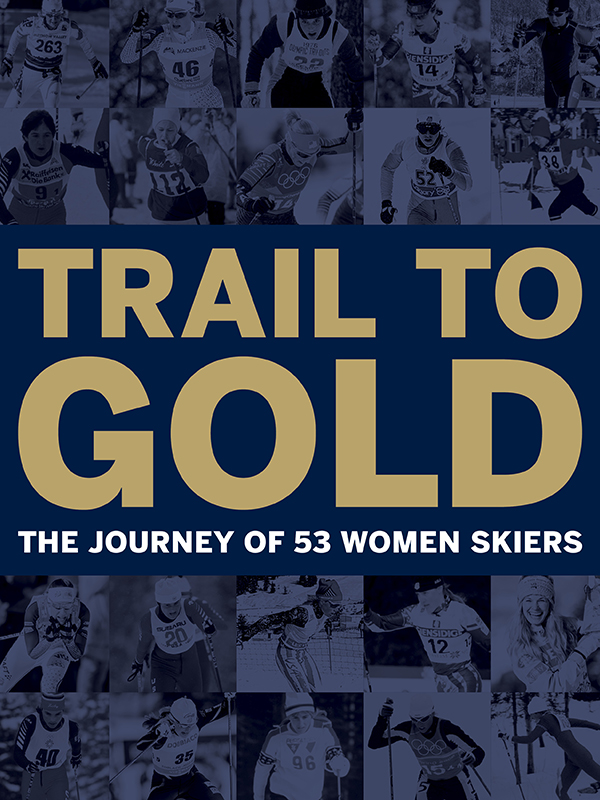

Jessie Diggins and Kikkan Randall made history when they took gold in the team sprint at the 2018 Winter Games, winning the first Olympic medal for U.S. women cross country skiers. But there was also history behind this win—the story of 51 other U.S. women who had competed for medals in cross country skiing.

Although they had come up short, these women laid tracks, so to speak, for Diggins’s and Randall’s eventual success. Trail to Gold: The Journey of 53 Women Skiers brings the stories of these women to light. Enhanced by great pictures, the book is not only a comprehensive history on U.S. women’s cross country ski racing but could also serve as a primer for anyone trying to achieve similar results in cross country skiing—or really any sport.

The book derived from a team-building exercise begun in 2013 by Matt Whitcomb, who was then the U.S. women’s head coach. He suggested to team members that they interview the female Olympians who had come before them, with the idea that those stories would both inform and inspire the current team. The list started with the five women who competed at Sapporo in 1972 (the first Winter Games to which the U.S. sent a women’s cross country ski team) and continued up to the 2010 U.S. Olympic team.

As the current athletes inquired about those experiences, the retired ski racers realized that their stories still mattered. About 40 of them gathered for a reunion in 2019 that was organized by three Olympians, Alison Owen Bradley (1972), Sue Long Wemyss (1984) and Randall. Wemyss eventually spearheaded a committee to pull together the women’s stories and photos for a book—Trail to Gold was born.

More than just a series of Olympic bios, the book captures each of these women’s voices. In one chapter, “Breaking Trail,” those first five Olympians share memories of their early days on cross country skis. There’s Margie Mahoney, for instance, skiing in the dark in Anchorage—in jeans. At age 13, Alison Bradley became the first girl to compete at junior nationals, but only after race officials decided that she was up to the challenge; they parked an ambulance nearby “in case my delicate female soul needed it,” Bradley recalls. The women’s first real taste of international competition came in 1970 when they traveled to Prague for the world championships, where the Soviets cleaned up.

Other chapters communicate the struggles these women faced as they trained and raced internationally: paying their own way, doing their own waxing, dealing with coaches who were more used to working with men, and facing the loneliness that comes when your teammates are also your competitors. Through the highs and lows, they made the best of it, finding inexpensive equipment in Scandinavia (boots for $14, skis for $21), borrowing small uniforms from the men’s team and, perhaps most importantly, finding joy in gliding over snow.

The book also illustrates what led to the U.S. women’s recent successes. Learning from other skiers on the World Cup tour in the 2000s, for example, helped Randall instill belief, first in herself, then by inspiring her teammates. But she didn’t do it alone. As Randall’s dad said when he met Wemyss at a World Cup in Quebec City, “So these are the shoulders that Kikkan stands on.”

Yes, Wemyss’s shoulders, along with those of many others whose experiences blazed the long trail to Olympic gold. —Peggy Shinn

Trail to Gold: The Journey of 53 Women Skiers, compiled by U.S. Olympic women cross country skiers from 1972 to 2018, Pathway Book Service, $35

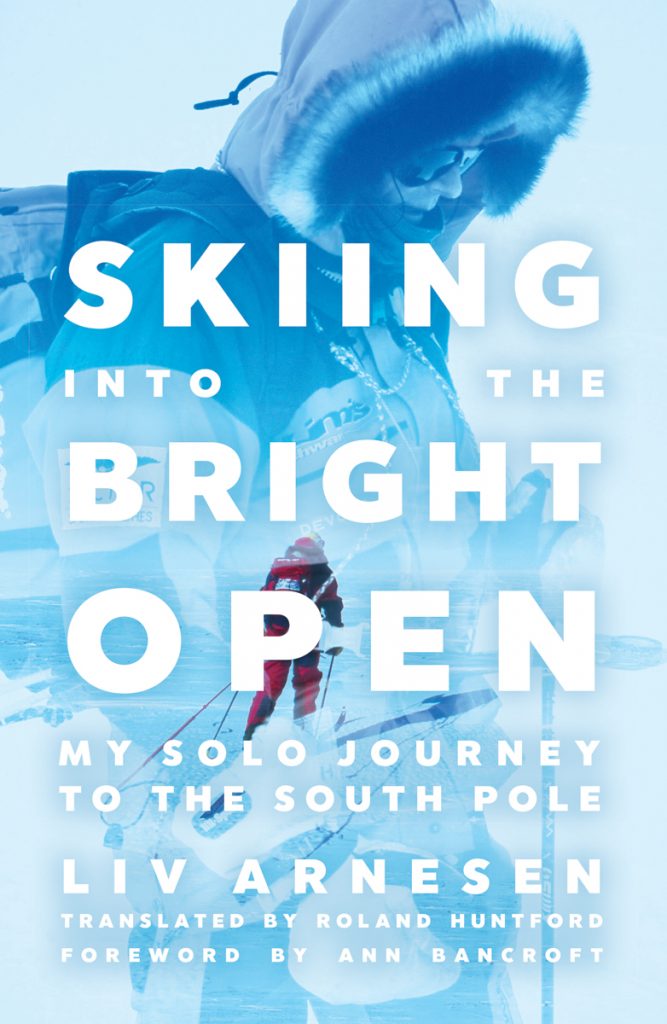

Liv Arnesen’s account of her 50-day unsupported ski to the South Pole—she was the first woman to do so—compellingly lays out the challenges she faced before and during the journey. But you had to know Norwegian to read it—until now.

Twenty-six years after Arnesen’s book was published comes this English translation; it includes a new foreword by Ann Bancroft, no slouch herself when it comes to polar expeditions. (She notes that getting funding for her own women’s voyage to the South Pole in the early 1990s “was considerably harder than life on the ice.”)

Drawn to adventure since she was a girl, Arnesen skied across the Greenland Ice Cap in 1992, two years before her South Pole expedition. That experience only whetted her appetite for the “great wide open spaces.”

Like Bancroft, Arnesen had to overcome resistance when seeking sponsors for the Antarctic venture. Her determination also helped her undertake a year and a half of training, which included dragging tires (well before CrossFit became a thing) to simulate the feel of the 220-pound sled she’d be pulling across the ice.

Not many people have the physical and mental stamina required for such an arduous mission. But by documenting her careful planning and preparation, Arnesen manages to make the adventures one dreams of seem within reach. —Cindy Hirschfeld

Skiing into the Bright Open: My Solo Journey to the South Pole, by Liv Arnesen, translated by Roland Huntford, University of Minnesota Press, $22

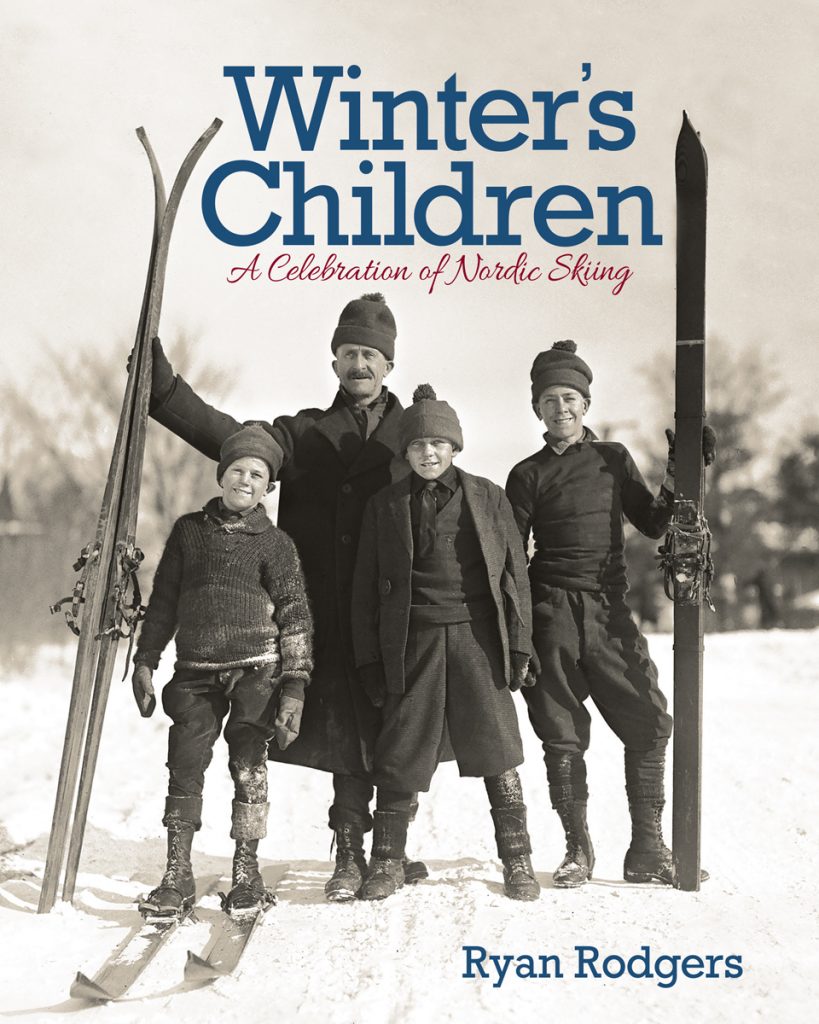

Minnesota-based writer and skier Ryan Rodgers takes readers on an entertaining journey as he explores the role cross country skiing has played over the years in the upper Midwest.

From the first known skier in the U.S.—a Norwegian immigrant in 1841 who set off a stir as people speculated about the odd parallel tracks he left in the snow—to today’s kids learning to glide with Minneapolis’ Loppet Foundation, Rodgers relates a comprehensive, richly detailed story.

Norwegians figure prominently in the account—no surprise—influencing technique, competitions and ski manufacturing as they settled in communities around the region. Ski clubs formed in the 1880s, and ski jumping contests—and eventually, races—drew hordes of spectators.

Accordingly, the Midwest had a lot of skiers. The first U.S. Ski Team, which went to the inaugural Winter Olympics in Chamonix in 1924, was mainly comprised of Midwesterners, with Minneapolis’ mayor as the coach.

After World War II, the burgeoning sport of alpine skiing eclipsed ski jumping and cross country in popularity. But in the 1960s, a second renaissance emerged, as skiers bemoaned the high price of alpine resorts and wanted to get back to nature. Races like the Birkie and the Mora Vasaloppet debuted in 1973.

Rodgers enlivens the history by focusing on the people who developed Nordic skiing, weaving together biographical info with anecdotes and including some 300 photos (a favorite: Spot, a ski-jumping dog in the 1920s). He’s also created a somewhat bittersweet paean to a type of Midwestern ski experience that is slowly fading away as natural snowfall decreases, even as artificial snow takes its place. —C.H.

Winter’s Children: A Celebration of Nordic Skiing, by Ryan Rodgers, University of Minnesota Press, $35

This story first appeared in the Early Winter 2022 issue of Cross Country Skier (41.2).